8 October 2022, by Sherri Mastrangelo

Even if your parents have not taken a DNA test, Ancestry DNA®’s new feature, Parental Matches, will now automatically group most of your matches to a maternal side and paternal side. This will help you confirm matches you already know, and possibly learn new matches and relationships. And what’s more - let’s say you have your mom take an AncestryDNA® test, and she allows you to see her test results - you will now be able to see all of her DNA matches sorted by parent too! Amazing!

Their announcement reads “AncestryDNA® is now the only DNA test that will automatically show which of your parents connects you to a DNA match, with or without a DNA test from one of your parents” with the disclaimer that “not all matches will be assigned to a parent”. This is based on their new SideView™ technology, announced last April. This new Parent Match feature launched October 5th

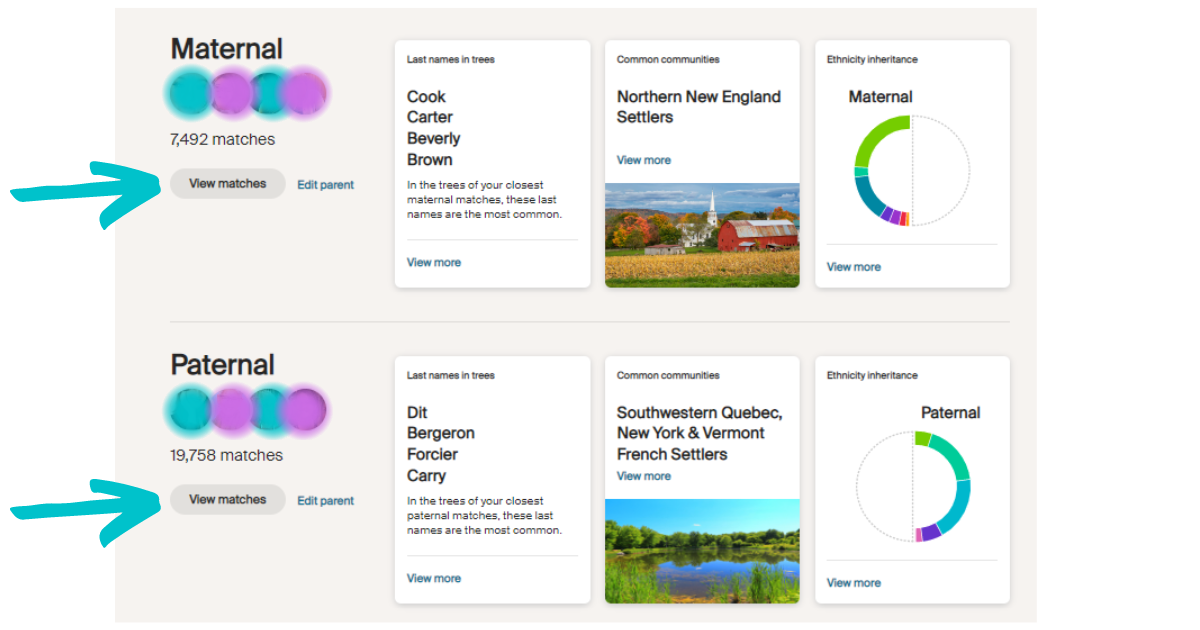

In my results, I still had 1,311 unassigned matches - a relatively small amount compared to my 7,492 maternal matches, and 19,758 paternal matches. At first glance, everything appears matched correctly. I should also note that I know only my father has taken a DNA test, and my mother has not - though other relatives on both sides have.

There is now an option to view DNA Matches by parent (marked “Beta”), in addition to all matches, or by location. On the first screen you’ll see a summary breakdown, with a short list of common last names, common communities, and ethnicity inheritance for both maternal matches and paternal matches. There is the option to view more in each section, but both the last names and common communities sections only give you slightly more information than the preview box.

Note - I blurred out the profile pics of some of my matches in the screenshot above, for their privacy. Click on “View matches” to see a list of your DNA matches assigned to either your maternal side or paternal side.

Below Maternal and Paternal, there most likely will be a section for Unassigned matches, that are not linked to either parent yet.

Also note that for some users it might be “Parent 1” and “Parent 2” instead of Maternal and Paternal, until you assign each parent a side by clicking the “edit parent” link. Hopefully you are able to quickly identify maternal vs paternal based on your family names and matches.

You may also have a section for “Both sides” for people that share DNA from both your parents, like your siblings, your children, nieces and nephews, or grandchildren.

View Matches

What you really want to do, though, is click “View matches” under each section. In the resulting list, you’ll see your DNA matches (sorted from highest to lowest match), each estimated relationship and amount of shared DNA, with links to their public tree (if available) and common ancestor (if there is one). Ancestry® also asks you to confirm the match and relationship level for each person.

Above: a screenshot of my DNA Matches on my maternal side (slightly edited to remove profile names and pictures).

You can also add each match to custom groups, which is an awesome feature. I also really like the ability to add notes for each person, so I can view their real name in this list (helpful when people on Ancestry® decide to use initials or randomness as their username). Any notes you add will show on this screen.

Keep checking back frequently, as the algorithms behind the AncestryDNA® feature improve and regularly update.

What do you think about this feature? Have you found it helpful in breaking down any brick walls, or making new matches?