3 October 2022, by Sherri Mastrangelo

Fraternal orders like the Freemasons, the Elks, and the Odd Fellows reached the height of their popularity in the 19th century, and many of our ancestors were members. These social clubs are well-known by outsiders for their secretive nature, as well as their use of symbols and mysterious rituals. They are also known for the benefits they bring through community service or charity work. Yet, like many groups of the time, these social clubs were originally for white people only - excluding African Americans (1).

These excluded people understood the value of these social groups for them, especially during and immediately post legal slavery in America, and found ingenious ways to create their own fraternal orders (which I’ll share below).

Modern researchers should understand these groups were often left out of city and social directories of the time (2), making it more difficult to find membership histories, but knowing which groups were popular and where will help you find specific lodges, which may keep their own records. Newspaper records, as well as African American created newspapers and directories, may also be helpful in your search.

Prince Hall Masons

The origin story of first African American fraternal order in the states, the Prince Hall Masons, should be taught more in history classes. Though many articles refer to him as a “West Indian immigrant”, Prince Hall himself was a former slave living in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1775, he and 14 other freed Black men were “made masons in Lodge #441 of the Irish Registry attached to the 38th British Foot Infantry…it marked the first time that Black men were made masons in America” (princehall.org). Shortly after the American Revolutionary War started, and when his infantry lodge went off to fight, Hall created African Lodge #1 under a special permit with limited privileges.

In 1784, having been rejected by other masonic leaders in America, Prince Hall petitioned the Grand Lodge of England for a charter to create a full masonic lodge. Surprisingly, so shortly after the American and British conflict, “the Grand Lodge of England issued a charter on September 29, 1784 to African Lodge #459, the first lodge of Blacks in America” (princehall.org).

Hall became Provincial Grand Master by 1791, soon after created another lodge in Philadelphia then Rhode Island, and African Lodge #459 became independent from the Grand Lodge of England by 1827. The success of the Prince Hall Masons grew, and “by 1865, there were more than 2,700 Prince Hall Masons meeting under the jurisdiction of 23 grand lodges in 22 states plus Canada and the District of Columbia…By the early 1900s, there were more than 66,000 Master Prince Hall Masons and another 51,000 apprentices…” then “from 1900 to 1930 the fraternity’s membership exploded” (Skocpol and Oser). Now there “are some 5,000 lodges and 47 grand lodges who trace their lineage to the Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Jurisdiction of Massachusetts” (princehall.org).

Further Research of the PHM:

The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge F. & A.M. of Massachusetts, (https://www.princehall.org/prince-hall-freemasonry/)

“Prince Hall Freemasonry: A Resource Guide” from the Library of Congress (https://guides.loc.gov/prince-hall-freemasonry)

“Constitution and By-Laws of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons” (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=emu.010000666967&view=1up&seq=3&skin=2021)

“Group of Grand Lodge Masons No. 2” c1897, Library of Congress. No known copyright restrictions.

Grand United Order of Odd Fellows

Like the Prince Hall Masons, a group of African Americans faced rejection from existing Odd Fellow groups in America. And “again, African Americans used a tie to England to do an end run around their racially exclusionary white countrymen. In the early 1840s, members of an African American literary club in New York City applied to affiliate with the white Independent Order of Odd Fellows (an offshoot of the English Manchester Unity Odd Fellows)” and with the help of Peter Ogden, member of a lodge called the Grand United Order, they were able to apply for a British charter from his order. (Skocpol and Oser). Hence this group, the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (G.U.O.O.F.), is not a part of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows in America (I.O.O.F.) at the time, but a separate parallel group with a charter from England.

By 1886, “they had already become the largest African American order, with 52,814 members meeting in more than 1,000 lodges spread across 29 states” (Skocpol and Oser). In addition, “the black Odd Fellows provided social insurance benefits; built social-welfare institutions as well as halls that served as meeting places for many black groups; engaged in impressive parades and ritual displays; and attracted the leading men as well as more humble members in countless African American communities” (Skocpol and Oser).

Note that the “Household of Ruth” is the female auxiliary branch.

Further Research of the GUOOF:

“The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in America” (https://guoof.org/)

Brooks, Chas. H. “The Official History and Manual of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in America, A Chronological Treatise” Philadelphia, PA. 1902. (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=emu.010000427966&view=1up&seq=7&skin=2021)

“African American man, member of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, wearing fraternal order collar and apron”. Library of Congress. No known copyright restrictions.

Knights of Pythias of North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa*

Not to be confused with the Knights of Pythias, this African American fraternal order with a longer name (sometimes referred to as “the Colored Knights of Pythias” in earlier texts) was another parallel group created out of necessity. The group was created in 1880, by Dr. Thomas W. Stringer, “a black Mason, African Methodist Episcopal minister, and Reconstruction-era Mississippi state senator” (Skocpol and Oser) and his associates in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

This time they did not resort to England’s help, but instead “a handful of black men who could “pass” racially gained admittance to a white lodge and appropriated its secrets “on the grounds that since the exclusion of colored men violated the purpose of the order, which was to extend friendship, charity, and benevolence among men, Divine Providence had made it possible for [them] to acquire the ritual” (Skocpol and Oser). In 1880, Lightfoot Lodge #1 was created in Mississippi.

*Note the group name would later include Australia. Sometimes referenced as “The Supreme Lodge of Knights of Pythias of North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia.”

Further Research of the KPNSAEAA:

“Knights of Pythias Files, 1903 - 1974” The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts. (In Person Research) (https://archives.nypl.org/scm/21064)

Peebles, Marilyn T. “The Alabama Knights of Pythias of North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia: A Brief History” 2012.

Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World

The IBPOE of W was established in 1898 by a former slave, Arthur James Riggs, with attorney Benjamin Franklin Howard, who had faced rejection from their local Elks when they tried to join. They “managed to procure a copy of the white Elks ritual” in Cincinnati, Ohio and form their own group based on the same principals and rituals (Skocpol and Oser). The new group added the “Improved” part of the name.

What’s more, they discovered the original Elks (the BPOE) had never bothered to copyright their name or rituals or anything, and so they were able to obtain a copyright themselves from the Library of Congress.

Members of the BPOE were not happy about this, and Riggs was threatened with lynching and forced to go into hiding. BF Howard was able to continue the group, and today the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks is one of the largest Black fraternal orders.

The women’s group is called the Daughters of the IBPOEW.

Further Research of the IBPOEW:

History of the Improved Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World (https://www.ibpoew.org/history)

Laxton, Ymelda Rivera. “The Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks of the World” December 3, 2020. Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library Blog. (https://nationalheritagemuseum.typepad.com/library_and_archives/improved-benevolent-and-protective-order-of-elks-of-the-world/)

Wesley, Charles H. “History of the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World, 1898 - 1954” Association for the Study of African American Life, 2010.

United Brothers of Friendship and Sisters of the Mysterious Ten

“The United Brothers of Friendship (UBF) grew from an originally male-only local beneficial society launched by a youthful group of free men and slaves in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1861” (Skocpol and Oser), and adapted through the Civil War as some members became freed. The Sisters of the Mysterious Ten (SMT) was formalized in 1878, though women had been participating earlier as well. As for size, “in the 1890’s, there were reportedly some 100,000 members in 19 states and 2 territories” (Skocpol and Oser).

Further Research of the UBF:

Gibson, W.H. “History of the United Brothers of Friendship and Sisters of the Mysterious Ten”, 1897. Louisville, KY. Bradley & Gilbert Company. (https://archive.org/details/brofriendsismyst00gibsrich/page/n3/mode/2up)

Ritual and Degree Book of the United Brothers of Friendship (https://archive.org/details/649717102.4767.emory.edu/page/n5/mode/2up)

The St Luke Penny Savings Bank, opened by the Independent Order of St. Luke. NPS.gov.

Independent Order of St. Luke

The Independent Order of St. Luke (IOSL) “first appeared in Baltimore in 1867 as a women’s beneficial society connected to the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church” (Skocpol and Oser), founded by a formerly enslaved woman named Mary Prout under the name the United Order of St. Luke. It later admitted men as well.

The IOSL was organized under Maggie Lena Walker, who took over in 1899, and “under her thirty-five year tenure, the IOSL expanded nationwide to twenty-six states and at its peak boasted 100,000 members. She was, at the time, the only woman known to be leading a major Black fraternal order” (NPS). The IOSL, with her leadership, established several local businesses tied to the order, including the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank.

Further Research of the IOSL:

“Independent Order of St. Luke” by the National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/independent-order-of-st-luke.htm#:~:text=and%20Early%20Years-,The%20Independent%20Order%20of%20St.,could%20not%20otherwise%20access%20it.)

“Independent Order of St. Luke” National Museum of African American History & Culture. (https://www.searchablemuseum.com/independent-order-of-st-luke)

Degree Ritual of the Independent Order of St Luke of Virginia, 1894, on Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/DegreeRitualOfTheIndependentOrderOfStLukeOfVirginia1894/mode/2up

The Grand United Order of True Reformers

The Grand United Order of True Reformers (GUOTR or U.O. of T.R.) was an “insurance-oriented fraternal group open to both men and women” (Skocpol and Oser) that was “founded in Richmond in 1881 by the Reverend William Washington Browne, a former slave and Union soldier who became a teacher, temperance organizer, Colored Methodist minister, and then African Methodist Episcopal minister” (Skocpol and Oser). The GUOTR also established local businesses, including the True Reformers Bank, the first Black-owned bank in the nation.

They called each of their lodges “Fountains”, with the main branch the Grand Fountain.

Further Research of the GUOTR:

Burrell, W.P. “Twenty-five years history of the Grand Fountain of the United Order of True Reformers: 1881 - 1905” 1909 (https://archive.org/details/twentyfiveyearsh00burr)

Hollie, Donna Tyler. “Grand Fountain of the United Order of True Reformers”. Encyclopedia Virginia. (https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/grand-fountain-of-the-united-order-of-true-reformers/)

Watkinson, James D. “William Washington Browne and the True Reformers of Richmond, Virginia” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 97, No. 3, “A Sense of Their Own Power”: Black Virginians, 1619-1989 (Jul, 1989), pp. 375 – 398. Published By: Virginia Historical Society. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/4249094) NOTE: Requires login with Jstor

International Order of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor

The International Order of Twelve Knights, was founded by Reverend Moses Dickson in 1872, in Independence, Missouri. Dickson “was born a free man in Cincinnati in 1824, was a Union soldier during the Civil War, and afterwards became a prominent clergyman in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.” (Croteau). He was also “the second Grand Master of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Missouri” (Croteau).

Dickson claims his International Order of Twelve Knights was founded by members of the Order of Twelve, a secret anti-slavery group in the South prior to the Civil War. Modern researchers question if his stories were attempts to rile up membership.

The International Order of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor may be best known for opening the Taborian Hospital in 1942, in Mississippi, with an all-Black staff of doctors and nurses, and serving Black patients.

This fraternal order no longer exists.

Further Research of the IOKDT:

Dickson, Rev. Moses. “Manual of the International Order of Twelve of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, containing General Laws, Regulations, Ceremonies, Drill, and a Taborian Lexicon” St Louis, MO. 1891. A.R. Fleming & Co., Printers. (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t9474ff52&view=1up&seq=5&skin=2021)

Croteau, Jeff. “Moses Dickson and the Order of Twelve”. 26 May 2008. (https://nationalheritagemuseum.typepad.com/library_and_archives/international-order-of-twelve-of-knights-and-daughters-of-tabor/)

Laxton, Rivera Ymelda. “International Order of Twelve”. Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library Blog. 1 August 2017. (https://nationalheritagemuseum.typepad.com/library_and_archives/international-order-of-twelve-of-knights-and-daughters-of-tabor/)

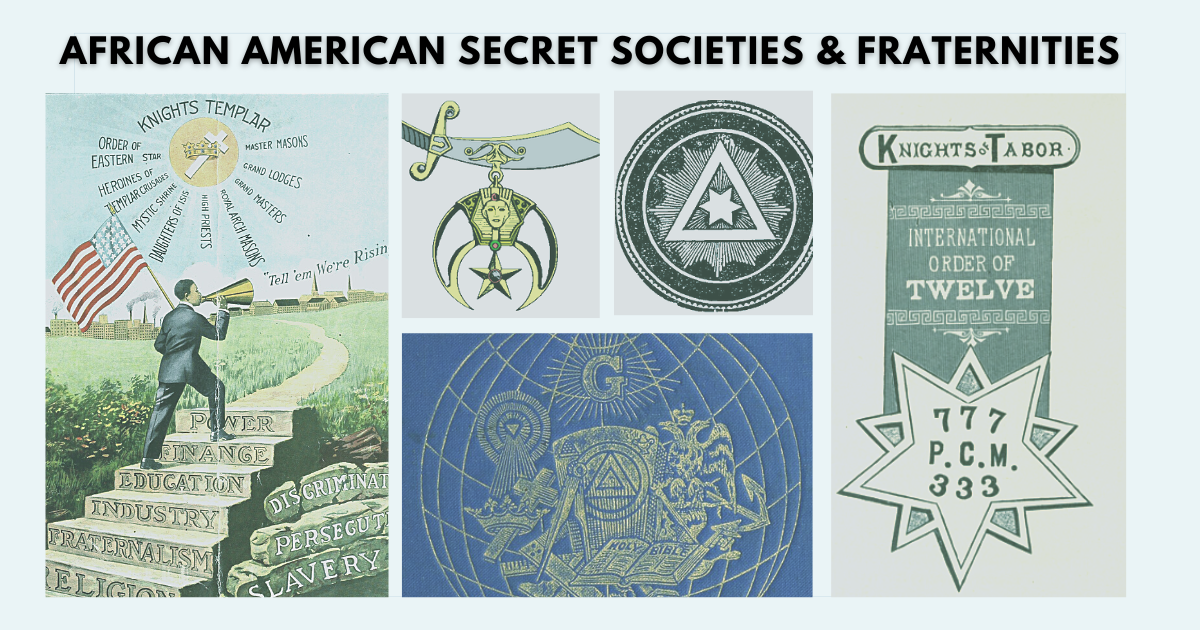

Additional African American fraternal orders and social groups included the Mosiac Templars of America (MTA); the Ancient Egyptian Arabic Order Nobles Mystic Shrine of North and South America; the Ancient United Order Knights and Daughters of Africa; the American Woodmen; Knights of the Invisible Colored Kingdom, and more. For a comprehensive list of groups, see the Skocpol and Oser article referenced.

Notes:

(1) An article titled “Organization despite Adversity: The Origins and Development of African American Fraternal Organizations” by Theda Skocpol and Jennifer Lynn Oser, shares that “prior to the 1970s, only a handful of major U.S. white associations were willing to accept African Americans as members” and that “the vast majority of U.S. white-led groups - above all, major white male fraternal groups, such as the Masons, the Odd Fellows, the Knights of Pythias, and the Elks - had explicit racial exclusion clauses in their constitutions or regularly practiced racial exclusion” (Skocpol and Oser).

(2) “National and local directories giving rich details about white voluntary associations between the 1870s and the 1920s often omitted most African American associations other than churches” (Skocpol and Oser)

Sources:

Croteau, Jeff. “Moses Dickson and the Order of Twelve”. 26 May 2008. (https://nationalheritagemuseum.typepad.com/library_and_archives/international-order-of-twelve-of-knights-and-daughters-of-tabor/)

PrinceHall.org. “A Brief History of Prince Hall Freemasonry in Massachusetts” The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge F. & A.M. of Massachusetts. (https://www.princehall.org/prince-hall-freemasonry/)

Skocpol, Theda and Oser, Jennifer Lynn. “Organization despite Adversity: The Origins and Development of African American Fraternal Associations” Vol. 28, No. 3, Special Issue: African American Fraternal Associations and the History of Civil Society in the United States (Fall, 2004), pp. 367-437 (71 pages) Cambridge University Press, (https://www.jstor.org/stable/40267851)

Stevens, Albert C. “The Cyclopedia of Fraternities…” 1899. (https://archive.org/details/cyclopdiaoffra00stevrich/mode/2up)

More Recommended Reading:

Grimshaw, William H. Official History of Freemasonry Among the Colored People of North America . New York, New York, 1903. (https://archive.org/details/officialhistoryo01grim)

Richardson, Clement. The National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race (1919). (The Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/19015870/)

Schmidt, Alvin J. Fraternal Organizations. Westport, Connecticut. Greenwood Press, 1980. (https://archive.org/details/fraternalorganiz0000schm/page/n15/mode/2up?q=%22grand+united+order%22)