by Sherri Mastrangelo, 26 April 2025

DuckDuckGo, Brave, Kagi, Mojeek… Swisscows? Are any of these alternative search engines good for your genealogy research?

Every good genealogist knows there is much more to research than an online Google search - most of the records you need are within databases, in books, or in offline record repositories. And yet we still need the web to find out where these records might be held, and how to access or request the needed information. We also may need the web to find and use the online tools needed to correlate our data, provide historical context, and research locations. We may need to look up other forms of data available online, like obituaries, newspaper articles, or even photos on social media. We may try to find others that are researching the same surnames as us, or even the same ancestors. We may try to connect with other researchers on forums, or within Facebook groups. We may even use the Wayback Machine to find websites or mailing lists that don’t exist anymore. There are many reasons to use the internet as a genealogist, and a search engine is going to help you find what you need.

A search engine, like Google, is an online tool that crawls the internet to collect information about websites, indexes that information, and then ranks and searches that index to try and give you the best results.

While Google currently sits at more than 86% of the search engine market share in the U.S. (per statcounter), it’s important to know that there are alternatives, and they may give you different results that may be useful.

Some are heavy on privacy, like DuckDuckGo or Startpage, but may not have as much advanced search features. Some, like Kagi Search, have privacy but aren’t free. Many are driven by other search engines, like Yahoo, and Ecosia, which are both empowered by Bing. Actually, Bing powers DuckDuckGo, Swisscows, and others too - as you can see on searchenginemap.com You can see Mojeek provides results for Kagi, which also pulls from Google (and Mojeek is not subscription-based, unlike Kagi).

So how would I rank all of these various options? Let’s test them, with genealogy! A quick reminder that this is NOT a sponsored post (though I use Adsense) and this rank is entirely my subjective opinion. With these test queries I tried not to use the AI search capabilities, if they were available, but I didn’t exclude it. The queries also use my own ancestors, because why not. I also included Google in the test, for comparison.

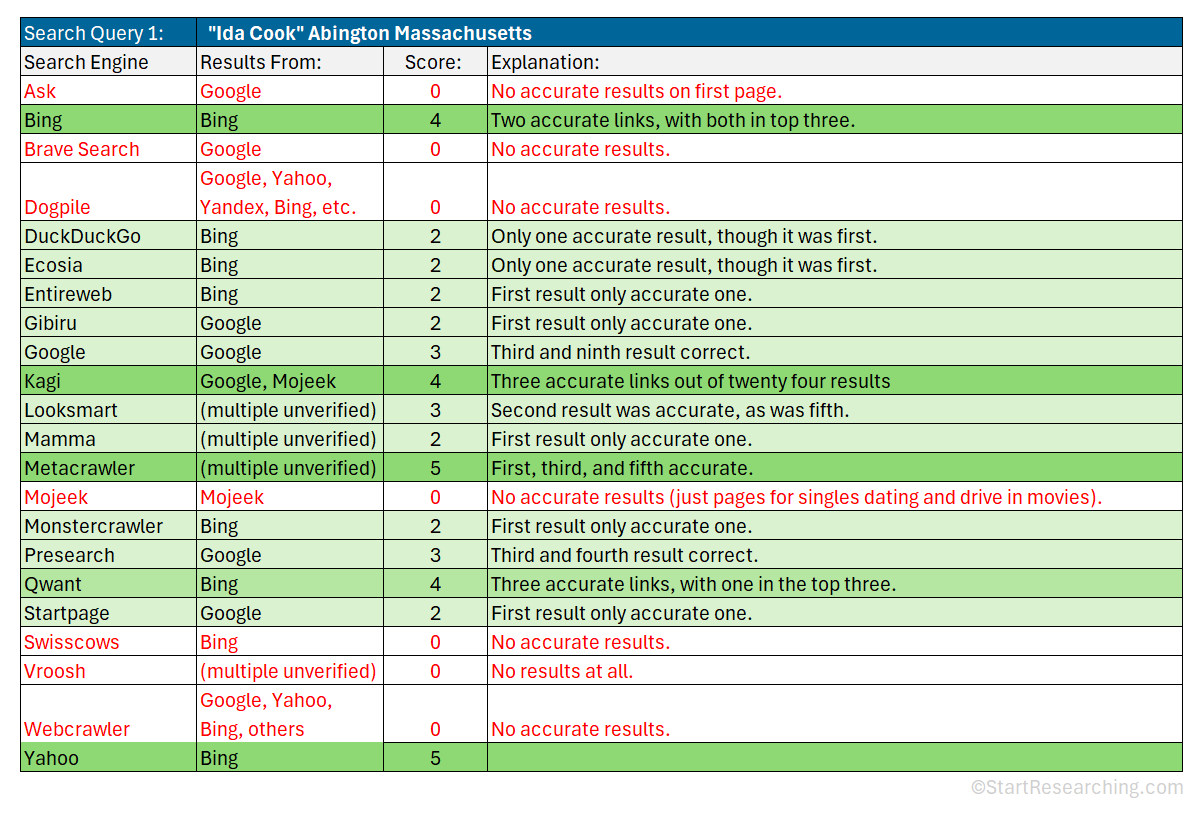

To keep score, I made up a point system :

+1 point for each accurate result link on the first page of results.

+1 point for any accurate links in the top three results, including any already counted, not counting sponsored results.

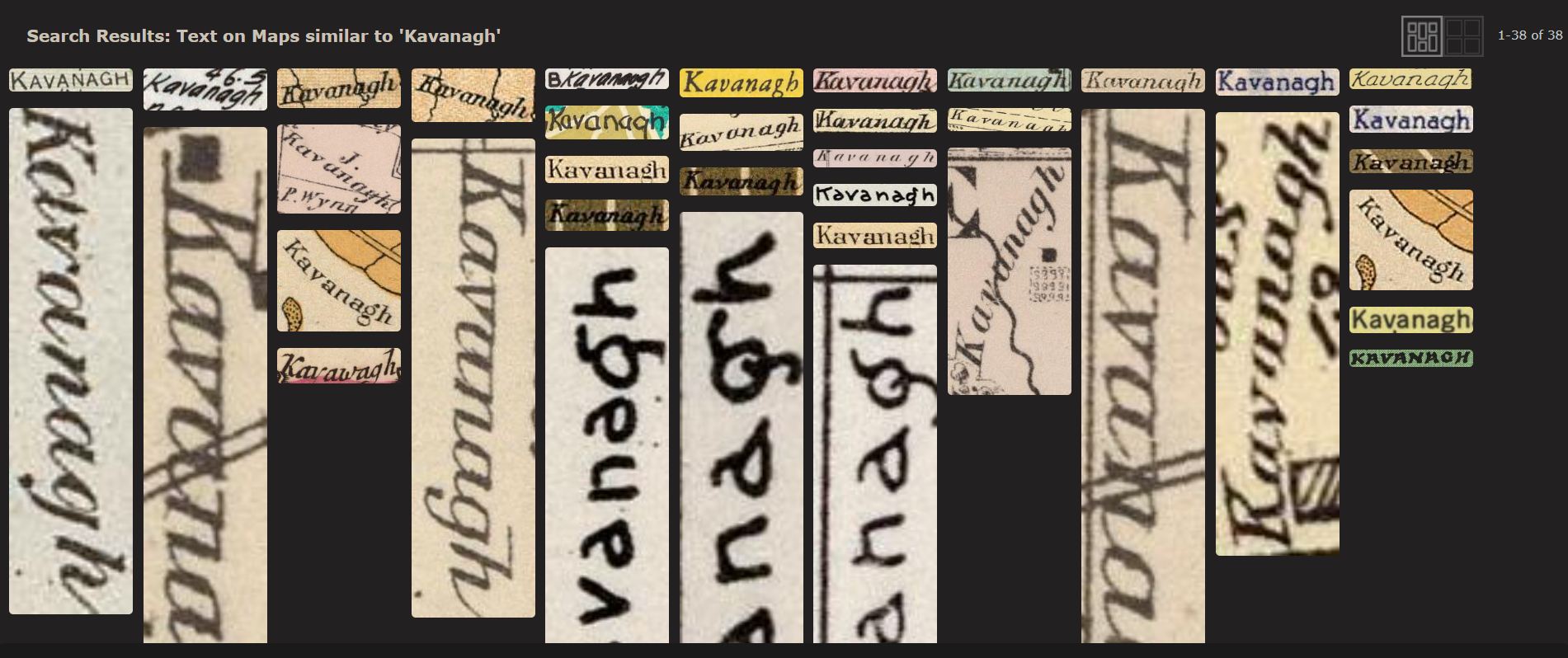

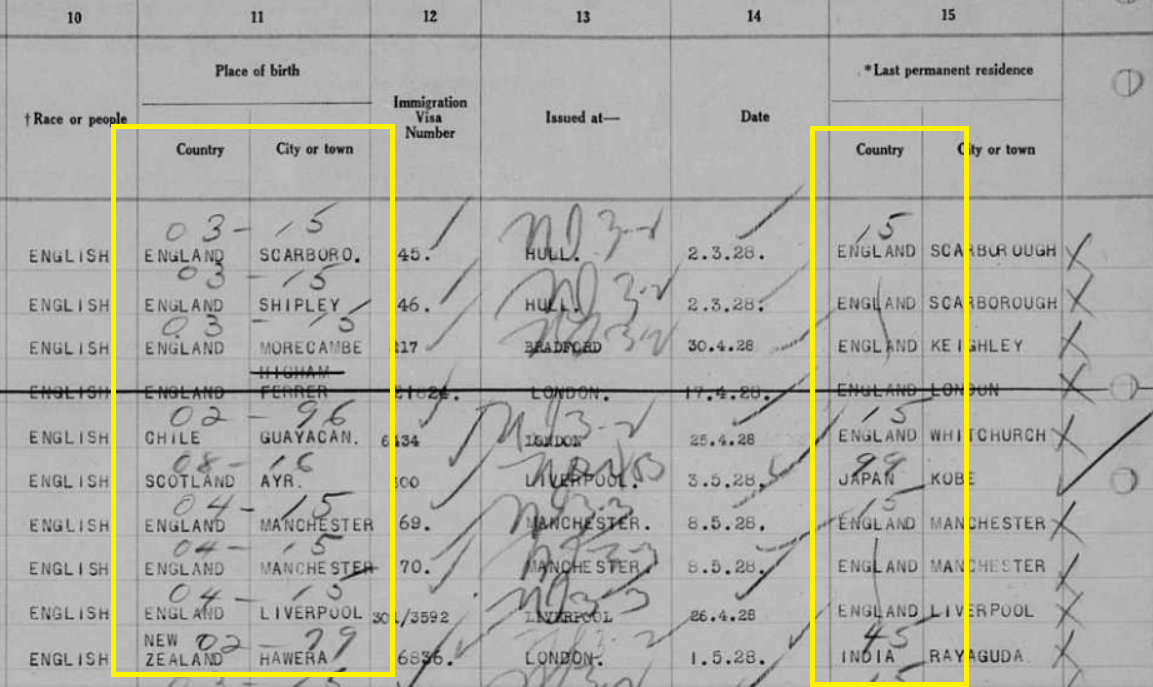

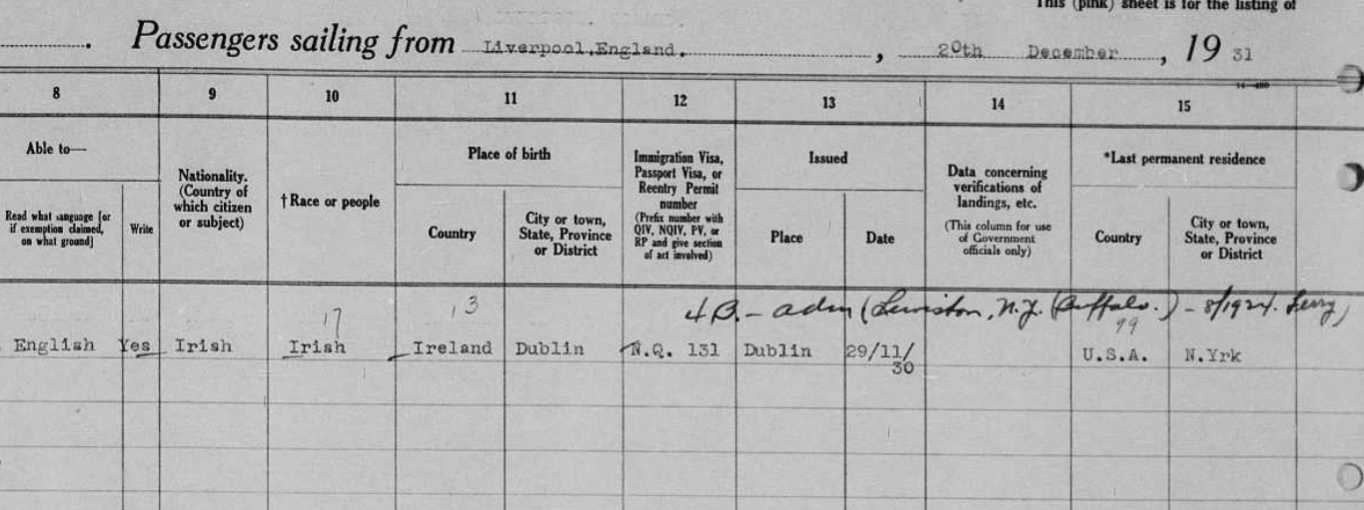

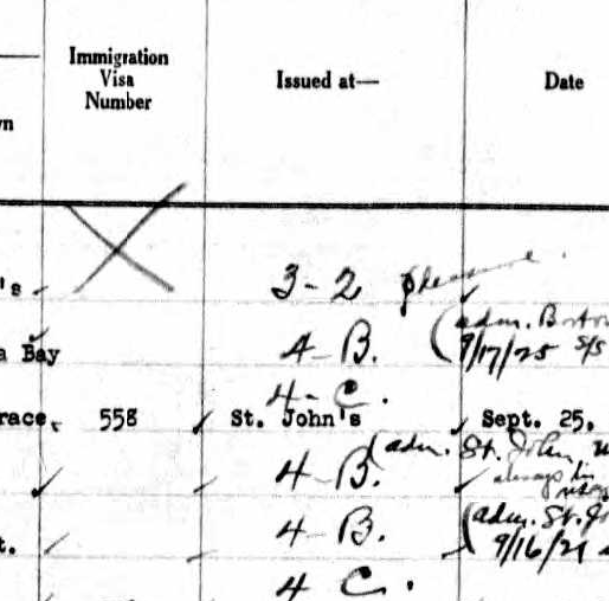

That’s it! I ran five tests, or search queries, on a multitude of search engines, as shown in the five images below. I did not use any search filters or advanced methods, other than quotations.

The winners the first round were Metacrawler and Yahoo with 5 points each, then Bing and Qwant with 4 points each. It looks like these are all powered by Bing (though I can't find an accurate answer about what drives Metacrawler, other than its multiple search engines). Data about which platform powers each is mainly from searchenginemap.com

Accurate results for this first query, of my great-grandmother Ida Cook (1894 - 1938), included her FindaGrave memorial page, as well as her daughter Phyllis’ obituary. While several links appeared relevant at first glance, I did not include them. These results are judged subjectively! For example, a newspapers.com article for an Ida Cook was a google result, but it was not from Massachusetts, and it was not my ancestor, so I did include it as accurate.

I dropped the search engines above that had no results, and continued on with the 15 below:

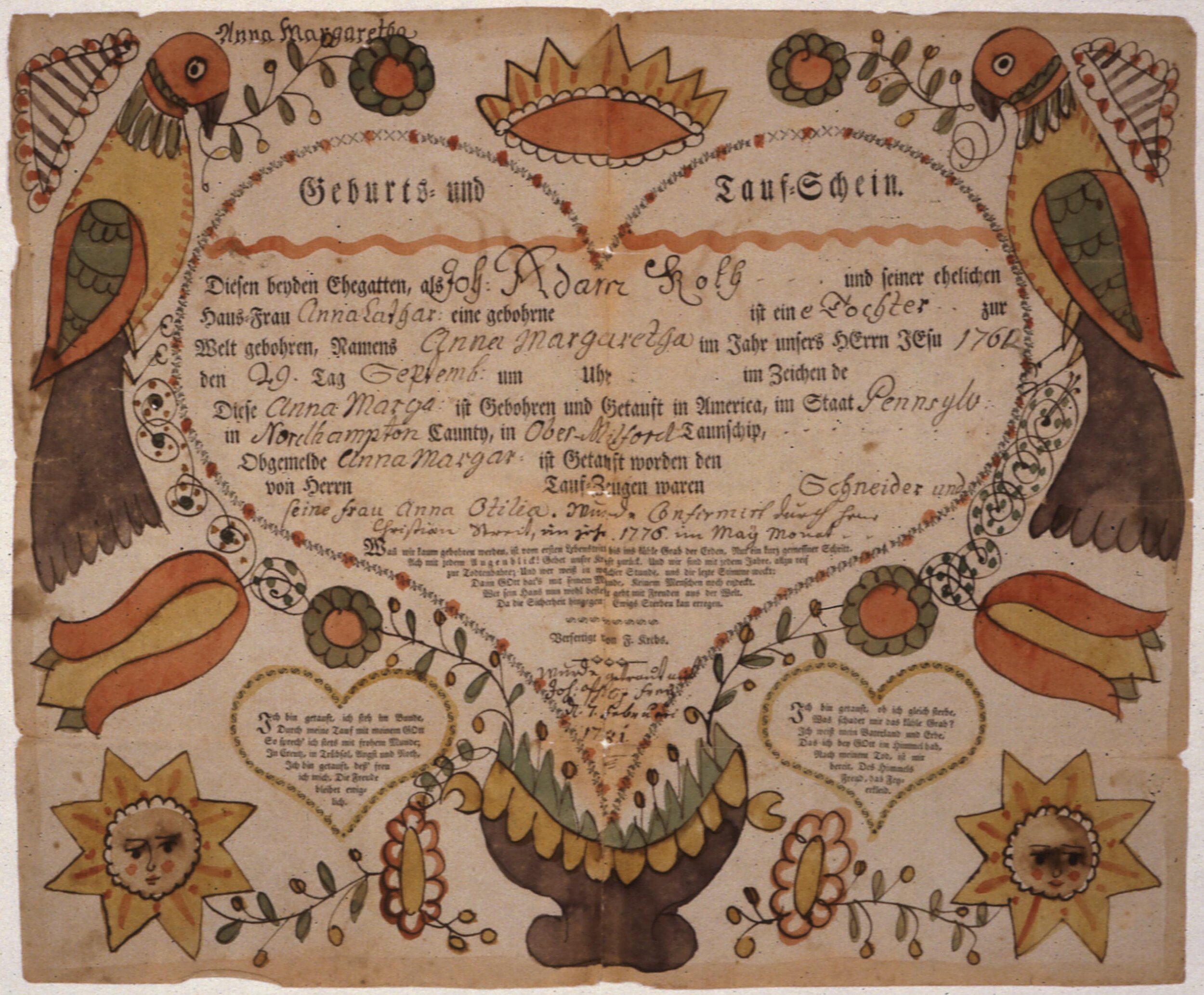

For the above search, accurate results included my ancestors with the Prunier surname from Yamaska (Elizabeth, Catherine, Martin, Jean, Antoine, Francouis, and many more). Results not counted were for the Prunier wine or restaurant in France, or for fruits and flowers.

I was very impressed by Gibiru and Presearch for the amount of quality results. Somehow both powered by Google, but did better than Google for accuracy - at least in my opinion.

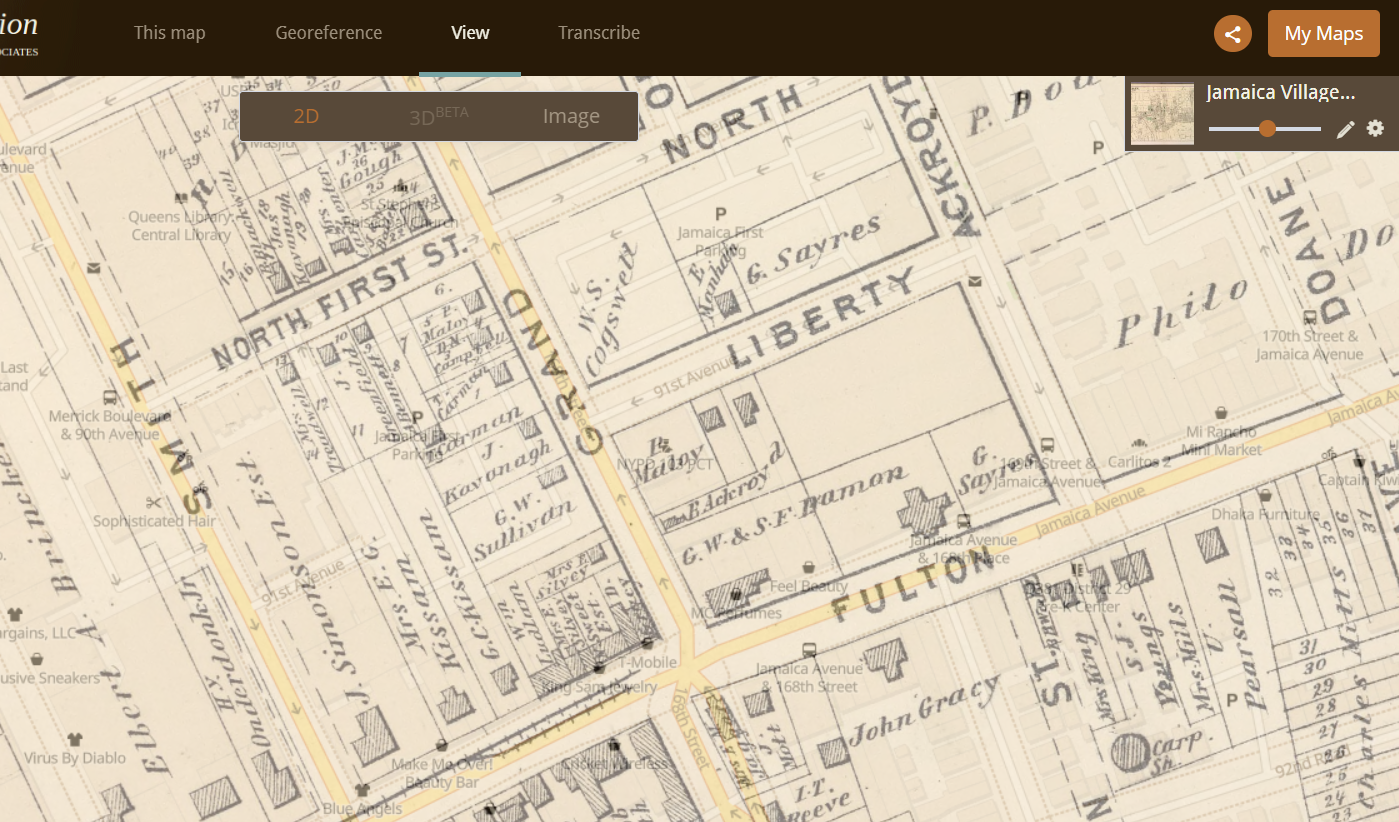

For the next query, we’ll go with something more generic, that a genealogist may need:

How did Kagi have 31 accurate results (with two in the top 3) all on the first page? And again, Gibiru and Presearch came in high.

Another generic query next, this time for Ireland records:

Kagi with 22 accurate results. Again, this post is not sponsored by anyone.

For the last test query, I’ll use another ancestor - my great grandfather, who was born in 1904 in Massachusetts and married to Alice Grandpre.

Interesting that many search engines did so poorly with this name. Looksmart did the best here.

And the winner is…..

Kagi in first, followed by Presearch, then Gibiru - all three came out ahead of Google. Kagi is a subscription search model, though you can sign up for a trial of 100 free searches with your email.

Will you be trying any of these three for some of your genealogy research?

Note: I did not include Yandex, as it is based in Russia (though you can search in English), or platforms in other languages like Baidu, Sogou, or Naver. I also did not include sites I couldn’t access, like SearchBoth, which gave me a too much traffic error, or AI platforms, like Search.com or Perplexity AI, or anything with an onion domain like SearXNG.